Do shipped chicks need heat lamps NOT brooder plates?

This post contains affiliate links for my favorite products from Amazon. As an associate, I earn from qualifying purchases at no extra cost to you.

One sad story I hear all too often from chicken keepers is that their shipped chicks all died—either shortly after arrival or within the next couple of weeks. Every year, my email gets flushed with these sad stories.

So, when my subscriber, Jackie, told me she’d had 25 chicks shipped to her and almost all of them died within just a couple days of arriving, I wasn’t surprised. Heartbroken with her, of course, but not surprised.

But then Jackie said a hatchery told her the reason her chicks all died had nothing to do with being shipped. It was because she used a heating plate for warmth (in a room with an ambient temperature of 75°), rather than using a heat lamp.

This explanation didn’t ring true to me because almost all the backyard chicken hatcheries and experts say you can use either a heat lamp or a brooding plate. Some even say never to use a heat lamp due to the risk of fire.

So, I decided to jump into the research science on shipped chicks to find out the truth about this.

Do shipped chicks require a heat lamp?

Shipped chicks require more heat for comfort than non-shipped chicks because body temperature is markedly lower in food-deprived (e.g., shipped) chicks. Adequate heat can be provided by 1.) a heat lamp or 2.) increasing the ambient temperature in the brooding room (in addition to a heat plate).

The truth is, most shipped chicks will survive without additional brooder heat, but weaker chicks (like Jackie’s) may not. If it takes your chicks a long time to get to you, if they experienced brutal shipping conditions, or if they were just a bit weaker to begin with, a warmer brooder may save their lives.

Regardless, all shipped chicks are likely to be more comfortable with a warmer brooder.

In this article, you will learn:

Why shipped chicks have lower body temperatures than non-shipped chicks

How much heat your shipped chicks need

How to provide additional heat as safely as possible

Or you can watch the video version of this blog post below:

The 2 things you need to know about your shipped chicks

#1 Shipped chicks are hungry chicks.

Let’s start with what I call the myth of the all-nourishing egg yolk sac. I’m sure you’ve heard it—it goes like this.

Myth: Newly hatched chicks are born with some of the yolk material from their egg still available for sustenance—it’s in their abdomens, and this yolk sac will completely nourish them for 72 hours without any outside food or water.

Have you heard that?

Well, here’s the truth.

In fact, the yolk sac is supposed to provide only 10-30% of the total energy and protein intake of a chick.5 Not 100%. 10-30%. The rest (70-90%) is supposed to come from actual food.

And actually, if food is available, chicks will choose to start eating just a few hours after they hatch, not 72 hours later.6

The research shows that by the time chicks are deprived of food for 48 hours, they’ve lost significant weight (rather than gaining weight as healthy chicks do).7-11

“Chicks that lose weight are presumably not eating and are in a state of starvation.”

What about food or GroGel in the shipping box?

I’ve seen YouTube videos where some backyard chicken hatcheries will throw a scoop of feed or some green nutritional gel into the shipping container for the chicks. But then they close the box up.

The problem here is that chicks are really unlikely to eat in the dark, closed box.

That’s what it takes to feed chicks during shipping.

Even the president of Murray McMurray Hatchery, one of the largest backyard chicken hatcheries, admits that the chicks probably aren’t eating the gel—he said in an interview:13

“In the transport boxes, I think it’s kind of defeated by just the sheer number of birds…typically, it just gets stepped on, and kind of mushed down…I’m not convinced it does a whole, anything as far as keeping them alive in transport…”

You can see the full interview below:

How shipping stresses amplify hunger

The chicks are already losing weight when they don’t eat, even in good conditions.

Add shipping stresses on top of that and your chicks just get more and more dehydrated and starved as they use up all their limited resources trying to cope with those additional stresses.

#2 Hungry chicks are cold chicks.

More recent studies have supported the finding that hungry chicks are cold chicks. One group of scientists says that if we take all this information from all these studies together, it "…leads to the hypothesis that a delay in feed access from the moment of hatch onwards impairs the thermoregulatory abilities of newly hatched chicks…"22

These scientists concluded:

“...if no feed can be provided after hatch for whatever reason, climatic conditions have to be adapted towards a higher environmental temperature to preserve the quality of the chick when placed on the farm.”

In other words, if chicks are being deprived of food, they need more heat.

That’s the gist of what you need to know.

Shipped chicks are hungry chicks, and hungry chicks are cold chicks.

Therefore, shipped chicks are cold chicks.

Why Jackie’s chicks may have needed more heat (case study)

Now Jackie’s story is starting to make more sense.

Jackie’s chicks also were transported during the winter in harsh conditions. We know harsh conditions further deplete the already-depleted resources of food-deprived chicks.14-20

Then, when Jackie’s chicks arrived, some of them were too weak to even stand. I’m going to leave out the specific details of what Jackie had to witness because they're quite distressing, but her description of her chicks perfectly matches the descriptions of chicks in the research studies who are starving to death.21

The research considers there to be 3 stages of starvation. Jackie’s chicks who couldn’t stand were likely in stage 3, and chicks don’t survive for long at stage 3. I really doubt there’s anything she could have done to save them that far into the starvation process.

The rest of Jackie’s chicks could at least stand, but they didn’t want to leave the brooder plate. So, even though they were starving, they were choosing to huddle under the brooder plate rather than eat.

“Heat conservation by huddling may be so strong a behavioral urge that it may discourage search for feed and water.”

No matter what. They just won’t eat. And they die.

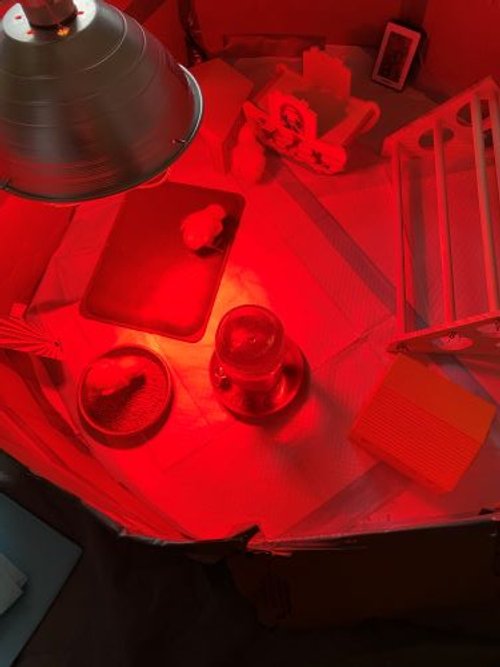

But Jackie did end up putting a heat lamp in her brooder to increase the temperature, and the remaining 3 of those 25 chicks did survive!

Jackie’s three surviving chicks under their heat lamp.

I can’t say for sure that any other of Jackie’s chicks would have lived had she had a heat lamp in there from the beginning, but it’s a definite possibility.

When do shipped chicks need more heat?

I’ve only shared a little of the scientific research here. The rest you can find in my blog post, Think twice about ordering chicks through the mail (the dire effects of shipping).

But after reviewing all the research, I’ve come to this conclusion:

For shipped chicks who are a bit older, who have had a rough journey, or who are just weaker for whatever reason, a warmer brooder may be the difference between life and death for those chicks.

And for all the other shipped chicks, the ones who aren’t in that horrible condition, they’ll likely benefit from a warmer initial brooder temperature as well. The research gives us every reason to believe that their body temperatures are lower than they should be.

How to give your shipped chicks the warmer brooder they need

In the past, I’ve always recommended a brooder plate in a room with an ambient temperature of about 75°. But after reviewing all the research, I’m now changing my recommendations for shipped chicks.

For shipped chicks, I now recommend you increase the ambient temperature in the brooder space.

There are two ways you could do this:

Use a heat lamp in your brooder. I, personally, am terrified of heat lamps. I worry about the fire hazards associated with them, but this may be the best option for you if #2 is impractical.

Crank the ambient temperature up in your brooder room, while still using a brooder plate within your chicks’ brooding space. This is the option I would choose.

Instructions for heat lamp users

If you are using a heat lamp, just follow the normal instructions for using a heat lamp, making the warmest spot of the brooder 95° for the first week.

Cackle Hatchery recommends you make the hottest part of your brooder 100-105°. However, they’re assuming that you have a large brooder, so that your chicks can get away from the heat if they need to do so.

But if your brooder’s fairly small (as many backyard chick brooders are), 100-105° is too hot. Your chicks run the risk of overheating.

Instructions for heat plate users

If you’re like me and you prefer using a brooder heat plate rather than a heat lamp, then you’ll also want to use a space heater to crank the ambient temperature up. I use a space heater in my brooding room that’s outside of the chicks’ small brooder space, and then, of course, I put a brooder plate in the small brooder space.

You’ll want to try to get your ambient temperature as close to 95° as you can for the first 3-4 hours of brooding. In order to get it that high, this may mean temporarily brooding your chicks in a smaller space that’s easier to heat, like a closet or a bathroom.

Even then, you may not be able to get the temperature that high. Just do the best you can.

During those first 3-4 hours at 95°, constantly supervise to make sure the chicks aren’t too hot. You’ll need to lower the temperature if they’re showing signs of heat stress, like panting or holding their wings out.

If your chicks are all eating and acting normally after 3-4 hours, lower that ambient temperature to 90°. Remember, you do still have the brooder plate that gives extra heat if they need it.

Then, if your chicks are still doing well after another 3-4 hours at 90°, lower that ambient temperature to 85°. Keep it at 85° for a few days. If everyone’s healthy, work on gradually lowering the ambient temperature more from there.

To recap, in addition to using a brooder plate:

Ambient temperature of 95° for 3-4 hours (with constant supervision)

Ambient temperature of 90° for 3-4 hours (with supervision)

Ambient temperature of 85° for 3 days

Slowly reduce the ambient temperature from there every week or so

At any of those stages, you could keep the temperature hotter for longer if you felt your chicks needed it. You just want to make sure they’re warm enough to get all the food they need.

Why do most chicken experts not recommend more heat for shipped chicks?

You’ll find that most major chick hatcheries and most well-educated chicken bloggers and authors aren’t recommending more heat for shipped chicks. As far as I can tell, Cackle Hatchery is the only large-scale chick hatchery that recommends more heat.

Most hatcheries (and experts) will say you can use a brooder plate in a room with an ambient temperature no lower than 50-60°. Wow!

Why do they think that’s warm enough?

For the same reason that I thought 75° was warm enough.

Because it usually is. Because the majority of shipped chicks aren’t on the brink of death.

The majority of shipped chicks can go warm up under that brooder heat plate, and then come out into the cooler ambient temperature to eat and drink just fine. They might be a little weak at first, but they catch up.

It’s when you get shipped chicks who are a little bit older when they get to you, or have gone through particularly brutal shipping conditions, or, for whatever reason, were a bit weaker to begin with—these are the chicks whose lives might be saved by a warmer brooder.

Even so, all shipped chicks will likely be more comfortable starting out with a warmer brooder, whether they’re on the brink or not.

And the truth is you never know what your shipped chicks have been through, which is why I recommend always playing it safe and raising that ambient temperature every time you get shipped chicks.

Good luck!

References

Murakami, H., Akiba, Y., and Horiguchi, M., “Growth and utilization of nutrients in newly-hatched chick with or without removal of residual yolk.” Growth, Development, and Aging, v. 56, no. 2, 1992, p. 75-84.

Santos, G. and Silversides, G., “Utilization of the sex-linked gene for imperfect albinism (S*ALS). 1. Effect of early weight loss on chick metabolism.” Poultry Science, v. 75, no. 11, 1996, p. 1321-329.

Panda, A., Bhanja, S., and Sunder, G., “Early post hatch nutrition on immune system development and function in broiler chickens.” World's Poultry Science Journal, v. 71, no. 2, 2015, p. 285-296.

Wang, J., Hu, H., Xu, Y., Wang, D., Jiang, L., Li, K., Wang, Y., and Zhan, X., “Effects of posthatch feed deprivation on residual yolk absorption, macronutrients synthesis, and organ development in broiler chicks.” Poultry Science, v. 99, no. 11., 2020a, 5587-5597.

Lamot, D., “First week nutrition for broiler chickens: Effects on growth, metabolic status, organ development, and carcass composition.” Ph.D. Dissertation, 2017, 192 p.

de Jong, I., van Riel, J., Bracke, M., and van den Brand, H., “A 'meta-analysis' of effects of post-hatch food and water deprivation on development, performance and welfare of chickens.” PLoS One, v. 12, no. 12, 2017, p. 1-20.

Nielsen, B., Juul-Madsen, H., Steenfeldt, S., Kjaer, J., and Sørensen, P., “Feeding activity in groups of newly hatched broiler chicks: effects of strain and hatching time.” Poultry Science, v. 89, no. 7, 2010, p. 1336-1344.

Warriss, P., Kestin, S., and Edwards, E., “Response of newly hatched chicks to inanition.” Veterinary Record, v. 130, no. 3, 1992, p. 49-53.

Malik, H., Ali, O., Elhadi, H., and Elzubeir, E., “Residual yolk utilization in fast and slow-growing chicks, subjected to feed and water deprivation.” Asian Journal of Biological Sciences, v. 4, no. 1, 2011, p. 90-95.

Pinchasov, Y. and Noy, Y., “Comparison of post‐hatch holding time and subsequent early performance of broiler chicks and Turkey poults.” British Poultry Science, v. 34, no. 1, 1993, p. 111-120.

Simon, K., de Vries Reilingh, G., Kemp, B., and Lammers, A., “Development of ileal cytokine and immunoglobulin expression levels in response to early feeding in broilers and layers.” Poultry Science, v. 93; no. 12, 2014, p. 3017-3027.

ampasturedpoultry. “Hatch Chicken Eggs in the Fall for Spring Layers.” 2021.

Olsen, M. and Winton, B., “Viability and weight of chicks as affected by shipping and time without feed.” Poultry Science, v. 20, no. 3, 1941, P. 243-250.

Schlenker, G. and Müller, W., “The transportation of day-old chicks by aircraft with regard to animal welfare.” Berliner und Münchener tierärztliche Wochenschrift, v. 110, no. 9, 1997, p. 315-319.

Mitchell, M., “Chick transport and welfare.” Avian Biology Research, V. 2, no. 1-2, 2009, p. 99-105.

Khosravinia, H., “Physiological responses of newly hatched broiler chicks to increasing journey distance during road transportation.” Italian Journal of Animal Science, v. 14, no., 3, 2015, p. 519-523.

Vieira, F., Groff, P., Silva, I., Nazareno, A., Godoy, T., Coutinho, L., Vieira, A., Silva-Miranda, K., “Impact of exposure time to harsh environments on physiology, mortality, and thermal comfort of day-old chickens in a simulated condition of transport.” International Journal of Biometeorology, v. 63, no. 6, 2019, p. 777-785.

Aviagen, “Factors affecting chick comfort and liveability from hatcher to brooding house.” 2021.

Yerpes, M., Llonch, P., and Manteca, X., “Effect of environmental conditions during transport on chick weight loss and mortality.” Poultry Science, v. 100, no. 1, 2021, p. 129-137.

Houpt, T., “Effects of fasting on blood sugar levels in baby chicks of varying ages.” Poultry Science, v. 37, no. 6, 1958, p. 1452-1459.

Willemsen, H., Debonne, M., Swennen, Q., Everaert, N., Careghi, C., Han, H., Bruggeman, V., Tona, K., and Decuypere, E., “Delay in feed access and spread of hatch: importance of early nutrition.” World's Poultry Science Journal, v. 66, no. 2, 2010, p. 177-188.

Danovich, T., “A ban on mail order chicks?” Modern Farmer, 2021.

East Bay Times. “Airline apologizes for death of turkey chicks.” 2006.

Özlü, S., Erkuş, T., Kamanh, S., Nicholson, A., and Elibol, O., “Influence of the preplacement holding time and feeding hydration supplementation before placement on yolk sac utilization, the crop filling rate, feeding behavior and first-week broiler performance.” Poultry Science, v. 101, no. 10, 2022, p. 1-11.

Xin, H. and Rieger, S., “Physical conditions and mortalities associated with international air transport of young chicks.” American Society of Agricultural Engineers, v. 38, no. 6, 1995, 1863-1867.

Hogan, J, “Development of food recognition in young chicks: II. Learned associations over long delays.” Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, v. 83, no. 3, 1973, 367-373.

Renwick, G. and Washburn, K., “Adaptation of chickens to cool temperature brooding.” Poultry Science, v. 61, no. 7, 1982, 1279-1289

Hamdy, A., Henken, A., Van der Hel, W., Galal, A., and Abd-Elmoty, A., “Effects of incubation humidity and hatching time on heat tolerance of neonatal chicks: growth performance after heat exposure.” Poultry Science, v. 70, no. 7, 1991, p. 1507-1515.